Minister of Tourism, Haim Katz launches the international travel fair IMTM 2026 (International Mediterranean Tourism Market) with the message “The Recovery is Already Here”. Well, it’s not.

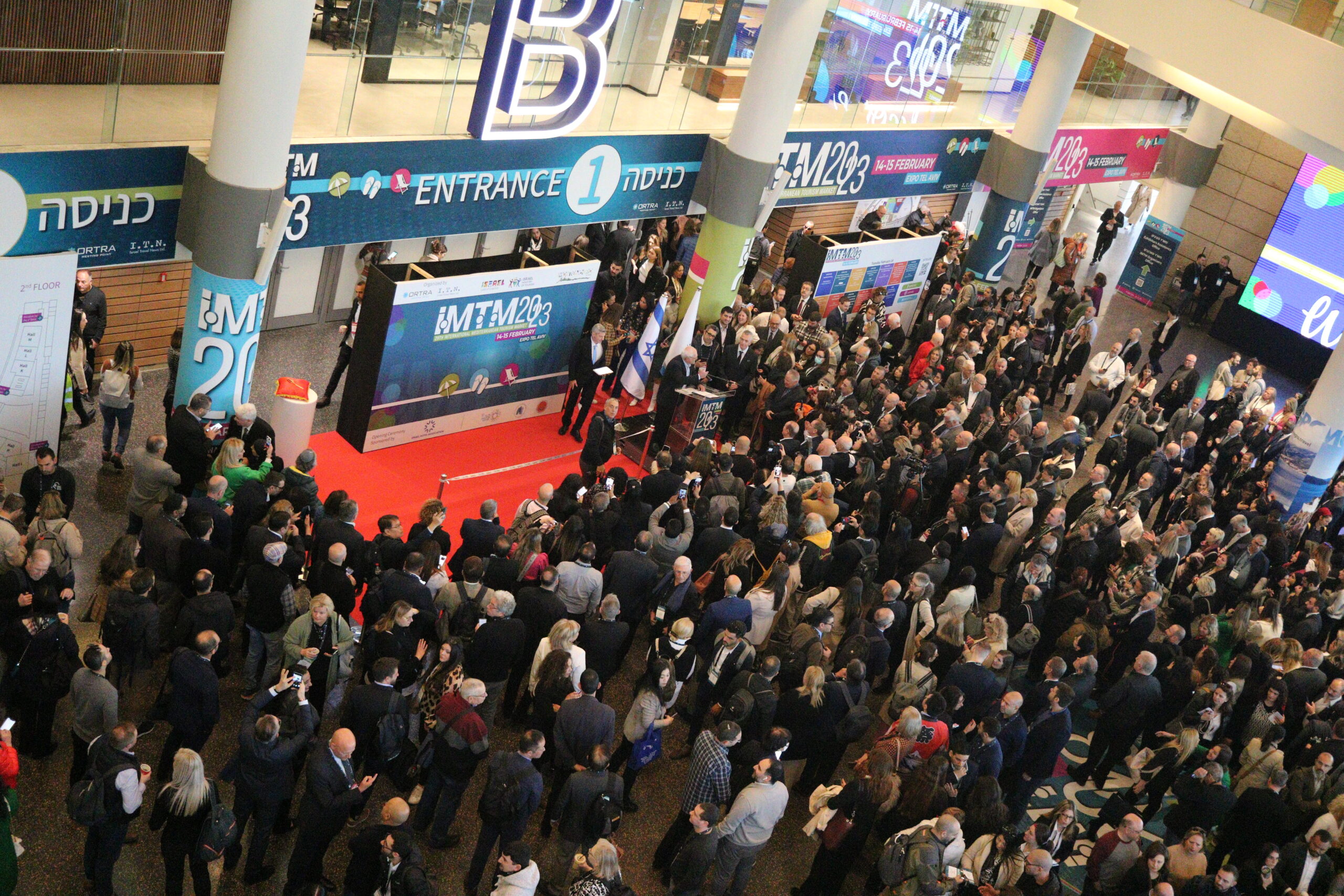

The first image shows the trade show floor of IMTM in February 2023 before the war in Gaza, we are not there yet, either by the number of IMTM visitors, or by tourism recovery.

The second image is IMTM 2026.

Calling this moment a “new era of tourism” may sound reassuring on a conference stage, but it collapses the moment you step outside the IMTM (International Mediterranean Tourism Market) halls and look at the actual map of Israel’s tourism economy. Recovery is not here, not in any meaningful, measurable sense, and especially not in the North of Israel, which remains effectively absent from the international tourism circuit. Declarations of optimism don’t fill hotel rooms in Tiberias, Metula, or the Galilee, and they don’t reopen shuttered guesthouses that have seen neither foreign visitors nor domestic confidence for well over a year now. What’s being presented as momentum is, at best, institutional hope wrapped in diplomatic language, the kind that sounds good but doesn’t survive contact with booking data.

Flight availability, repeatedly cited as proof of recovery, is actually the weakest link in this narrative. Israel today is not experiencing a normalization of air connectivity; it is experiencing a narrow funnel. The only budget airline currently operating in Israel is Wizz Air, and even that presence is cautious, limited, and tellingly absent from IMTM itself. Low-cost carriers are not a side detail in modern tourism—they are the backbone of mass inbound travel, particularly from Europe. When Ryanair, easyJet and others are missing, the signal is clear: tourism demand is still considered too fragile, too risky, or too unpredictable to justify a return. You cannot credibly argue recovery while the market’s volume drivers are staying away.

The North of Israel remains the clearest counterexample to the recovery narrative. Tourism is not “returning” there because it never restarted. Entire regional ecosystems—guides, small hotels, wineries, attractions, transport services—are frozen in limbo. International tourists are not booking multi-day stays in areas perceived as unstable, regardless of how polished the messaging sounds in Tel Aviv. Domestic tourism, often invoked as a substitute, cannot replace foreign inflows at scale, and it certainly cannot sustain regions that were built around international seasonal demand. Renovated hotels mean very little if there are no guests willing, or able, to reach them.

Even the country’s most resilient tourism hub quietly undermines the recovery story. Eilat has effectively switched to a domestic-only model, not by strategic choice but by necessity. International tourism there is marginal, episodic, and unreliable. Hotels that once relied on foreign charter flights now cater primarily to corporate retreats, conferences, and organized business groups, pricing themselves accordingly. The result is a city that technically has high occupancy at times, yet is increasingly inaccessible to the majority of Israelis. For many families, Eilat has become prohibitively expensive, less a national vacation destination and more a controlled, premium enclave designed around companies, not travelers. This is not recovery; it is a survival pivot that reshapes the market downward.

Marketing campaigns in the United States and diplomatic photo-ops with Mediterranean partners may strengthen political goodwill, but they do not resolve structural constraints. Tourism is not revived by slogans; it is revived by aircraft rotations, insurance underwriting, tour operator commitments, and traveler confidence measured in bookings, not applause. Regional cooperation looks good on paper, but symbolic alignment does not automatically translate into reopened routes, charter schedules, or international itineraries that include Israel’s periphery.

IMTM 2026 projects resilience, and resilience is real. The industry has endured, adapted, and avoided collapse. But survival is not recovery. Recovery implies accessibility, scale, affordability, and geographic breadth—and none of those conditions are fully present today. Until airlines return in force, until the North re-enters travel plans, and until destinations like Eilat are viable again for ordinary Israelis rather than just corporate budgets, claims of a tourism comeback remain premature. Optimism may be understandable, but accuracy matters more. Without it, the danger isn’t pessimism—it’s building policy and expectations on a reality that hasn’t actually arrived.

Leave a Reply