Year Zero unfolds like a quiet reckoning with the moment just before everything broke, when culture still believed in continuity and institutions still assumed tomorrow would resemble today. At the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, the exhibition looks back to the eve of World War II and reconstructs the fragile chain of decisions, memories, and acts of persistence that allowed modern art to survive displacement and annihilation. At its emotional core stands Dr. Karl Schwarz, the museum’s first director, who in the late 1930s embarked on what can only be described as a desperate final journey through Europe. Schwarz was not collecting opportunistically; he was searching for something he had seen in his youth in Berlin, a work that had stayed with him as the political and moral climate darkened. He traced it to Amsterdam and persuaded its owner to send it to Tel Aviv, an act that now reads as both practical and symbolic. That single rescue echoes through the exhibition, because between 1933 and 1945 Schwarz saved thousands of works under similar conditions. These paintings and sculptures, removed just in time from a continent turning hostile to their creators, became the nucleus of the museum’s Modern Art Collection. Year Zero is not interested in triumphal narratives; it is about the thin margin between preservation and erasure.

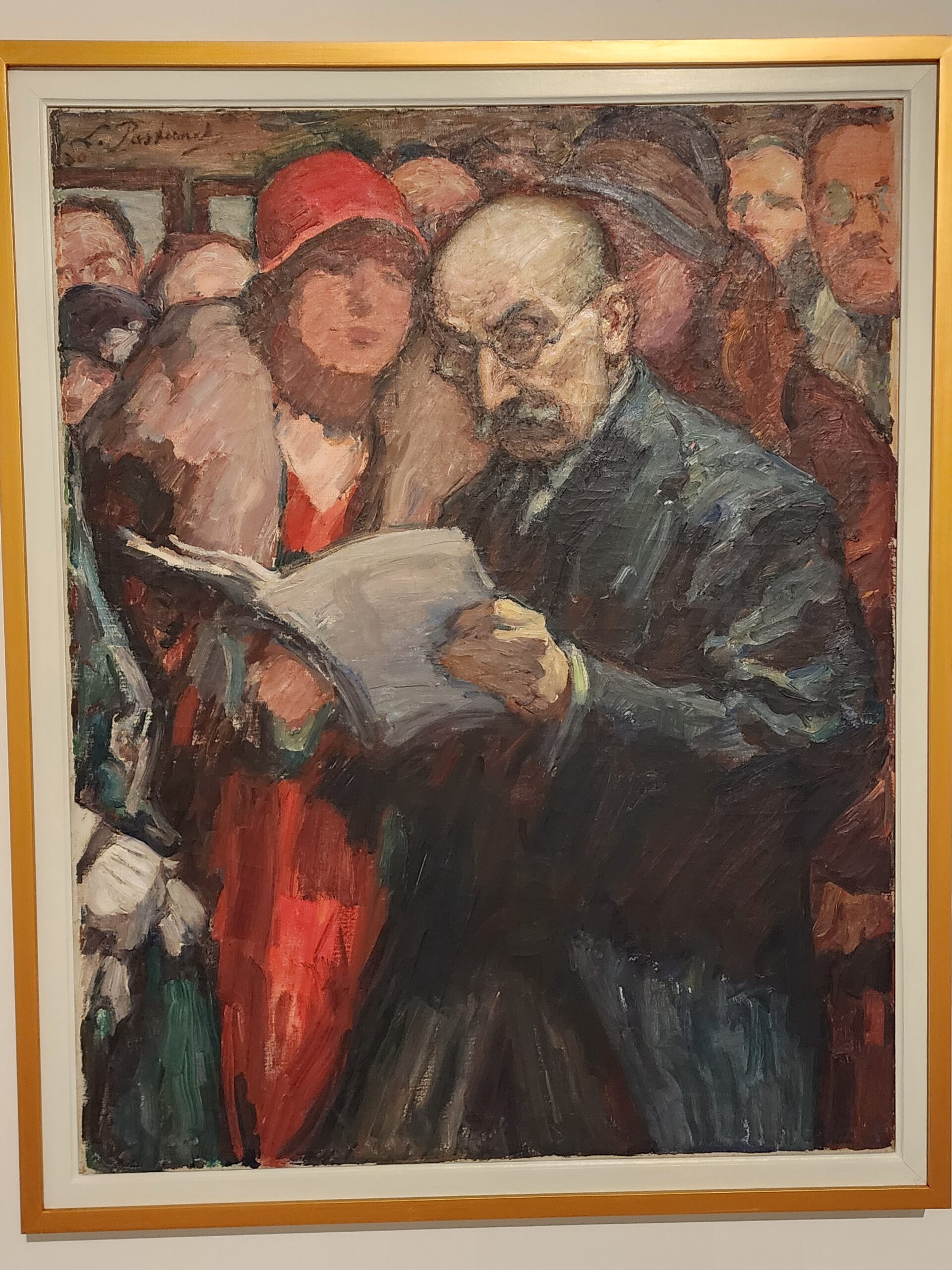

One painting crystallizes this tension with almost unsettling clarity: Leonid Pasternak’s Max Liebermann Opening an Exhibition at the Academy in Berlin, 1930. The canvas is dense, crowded, and inward-looking, its figures pressed together in a compressed social space that already feels unstable. Max Liebermann sits at the center, bald, bespectacled, bent over a sheet of paper, his attention fixed, his posture heavy with thought. Around him, faces emerge and dissolve into thick, restless brushstrokes—earthy browns, muted blues, sudden reds that flare and then retreat. A woman in a red hat stands just behind him, her features softened and unfinished, while other figures stack into the background, their individuality partially erased by proximity. The brushwork is rough, almost impatient, as if solidity itself were no longer trustworthy. Painted in 1930, the scene captures a cultural ceremony at the very edge of collapse, an academy still functioning, an exhibition still opening, even as the conditions that made such gatherings possible were already unraveling.

The painting gains another layer of meaning once you step slightly outside the frame. Leonid Pasternak was the father of Boris Pasternak, the author of Doctor Zhivago. That biographical fact creates a quiet but powerful bridge between visual art and literature, between this crowded Berlin interior and the sweeping moral landscapes of a novel that would later grapple with revolution, exile, and the endurance of private conscience under historical violence. Doctor Zhivago is haunted by the same tension visible in the painting: cultivated people absorbed in art, love, and thought while vast forces reorganize the world around them with little regard for individual lives. Seen this way, Pasternak’s painting reads almost like a visual preface to his son’s literary universe, a frozen moment of cultural concentration before history intrudes with full force. Father and son, each in a different medium, end up documenting the same rupture from opposite sides of time.

Year Zero extends this logic across the galleries, bringing together works by Alexander Archipenko, Marc Chagall, Käthe Kollwitz, and others not as isolated masterpieces but as survivors. The exhibition marks the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II, yet it deliberately lingers in the years just before the war, when outcomes were not yet sealed and individual actions still mattered. Many of the figures in these works are reading, thinking, grieving, or simply enduring, their gazes turned inward rather than outward. The cumulative effect is not nostalgia but unease. These are not heroic images; they are records of concentration, doubt, and fragile normalcy. What emerges is a portrait of modern art shaped not only by innovation and rebellion, but by rescue—by people who understood that culture does not survive on its own. Walking through Year Zero, you begin to sense that modernism, as preserved here, is less a story of progress than of narrow escapes, and that the survival of these works is inseparable from the moral clarity of those who refused to let them disappear into the noise of history.

Leave a Reply